Prisoners in Los Angeles put out fires for a few dollars a day

Written by Frauke Steffens, New York, Culture Correspondent for Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung. 16.01.2025 Link to original article follows this English translation.

Prisoners are also currently fighting the fires in California – the state is saving millions. The artist Kim Abeles worked with imprisoned firefighters a few years ago and gained insight into their lives.

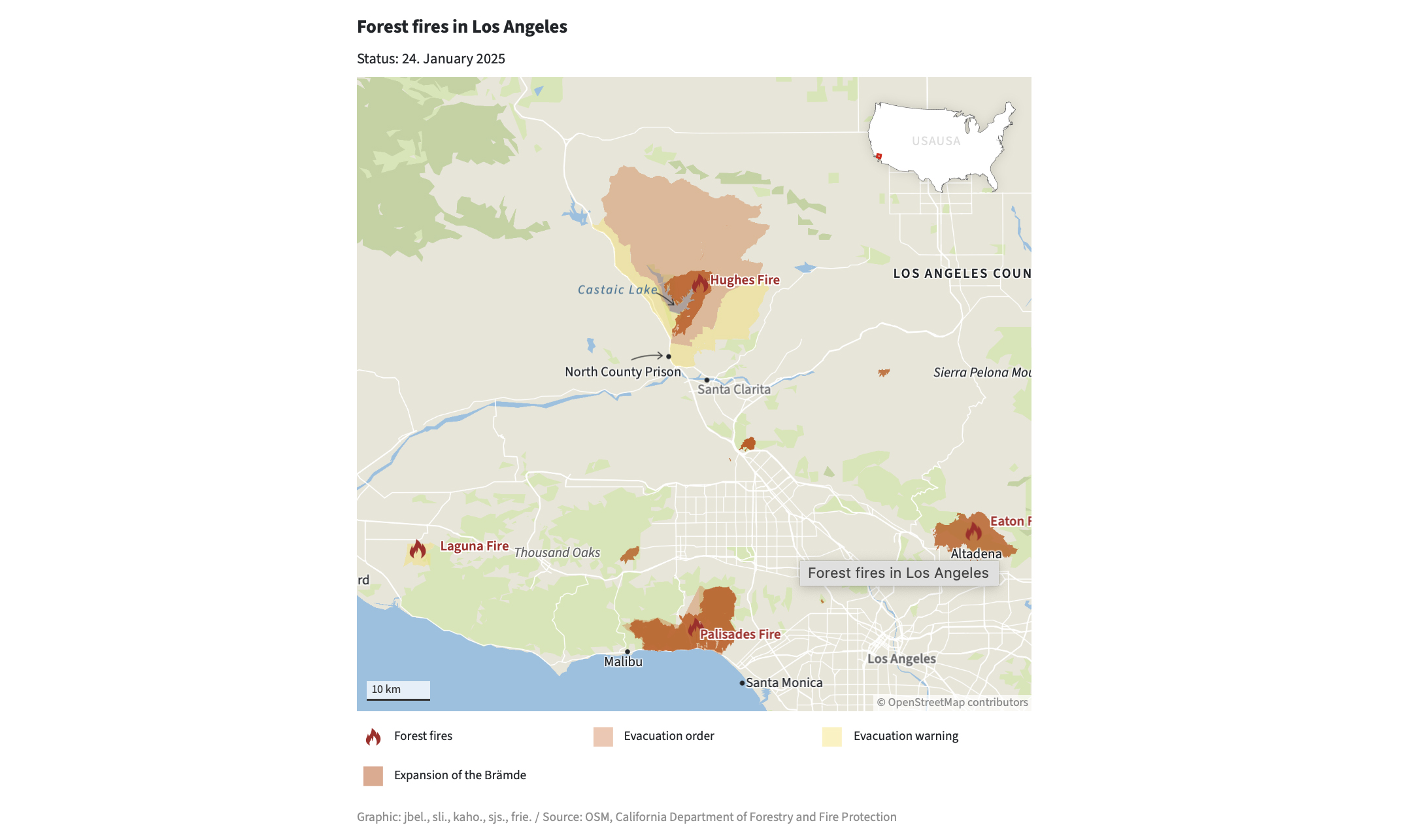

When Kim Abeles walks up the street in Pasadena a few blocks from her house, she can see the destruction: offshoots of the fire that destroyed hundreds of houses in neighboring Altadena have also raged in her neighborhood, set fire to trees, damaged buildings and cars. Everything is covered by a layer of ash, says the artist on the phone. She has just arrived in Denver to prepare an exhibition, but in her mind is with her family.

People in Los Angeles are particularly afraid of the flying embers, which can ignite new fires at any time. Abeles also often thinks of the 7,000 firefighters who fight the fires day and night. A few years ago, she worked on a project with imprisoned women at the fire department. Even now, more than 1100 prisoners are working against the disaster - it is unknown how many women are among them.

Of the vulnerability of nature

Due to the devastating fires in Los Angeles, public interest in the imprisoned firefighters is high again. Media report on their living conditions, celebrities such as Kim Kardashian call for better payment and for the punishment. The highest wage for the prisoners is $10.24 per day, for assignments like the one in Los Angeles they get an additional dollar an hour. Too little to compare to the average annual wages of California firefighters – $60,000 to $80,000.

Seven years ago, Kim Abeles spent a lot of time with imprisoned firefighters. For six months, she went to Camp 13 every week, one of 35 California Fire Camps, where prisoners live and are trained for their missions. This was possible because Abeles worked with the authorities. The national cultural foundation "National Endowment for the Arts" supported the project. In the workshop of "Camp 13" located in the forest, the women crocheted, painted and soldered together. Abeles often makes the relationship between man and environment the focus of her works. The former Guggenheim Fellow, which exhibited in museums around the world, became known as the "Smog Collectors" in 1987. A series of everyday objects made the smog around them visible.

From the prisoners in "Camp 13", Abeles wanted to know what the people "outside" should learn about the fires, about them and the job. The mixed media works that were created are called "Valises for Camp Ground", for example: "Suitcase for the Camp". They are dioramas that tell of the vulnerability of nature, of its unpredictability and of the means by which man wants to protect himself. A forest landscape or the model of a house can be seen there, divided in two, once deceptively safe and once turned gray from fire. In the workshop, Abeles learned a lot about the women's life stories. It was forbidden to take pictures or photos, says the 72-year-old artist. Being dependent only on notes made her particularly attentive.

The state saves 100 million dollars every year

Many of the prisoners are very proud of their job. If they were not fighting active fires, they climbed inaccessible areas to clear bushes, for example. Or they help with prevention on buildings – inreplaceable services to the community. Some of the women's children would talk about their mothers as heroines, says Abeles. They often described their work as meaningful, and many gained new self-confidence. Some former prisoners have also reported on this pride in interviews in recent days.

Ex-inmates who had worked for the fire department also spoke out on social media and wrote that they wanted to correct false reports. For example, the claim still circulates about the imprisoned firefighters in California that they should not take up a job in a fire department after their release from custody. Governor Gavin Newsom had abolished this policy at the end of 2020 - probably because the pandemic made the shortage of skilled workers clear with new urgency.

Above all, the state is saving a lot of money by using prisoners to protect against fire – about 100 million dollars every year, according to The Atlantic magazine. Critics say this is an incentive to sentence people to prison terms and to delay their release. There are actually always indications of this. For example, the California Ministry of Justice stated in 2014 that caution must be taken in the reform of the bail payments of prisoners, as staff shortages could arise in the fire department. The head of the authority at the time was the current vice president Kamala Harris, who later revised the position.

The prisoners are not forced

Kim Abeles is also critical of prison work, but she also emphasizes the resilience of the women she met. Several were able to use the job as firefighters to acquire new skills. Even in a cooperative art project like the "Valises", which have since toured many museums, it is always about learning from each other. For example, she could not crochet herself, says Abeles - some women took the lead and taught the others.

Living in nature instead of behind prison walls, with better food and more freedom than other prisoners, that's the decisive factor for many prisoners to register for the dangerous jobs. They are also credited with detention days under certain circumstances. The inmates are therefore not forced, only the basic start of a job can be prescribed by the state. This is because the United States is the 13th. Amendment not, which abolishes slavery, but further allows it as a punitive measure. In some states, the prison systems therefore even lend prisoners to private companies.

Critics see the extremely cheap labor for the state above all as part of the "prison-industrial complex". The authorities and companies could use an inexhaustible reservoir of labor, which mainly draws from the mass incarceration of poor and non-white people. In freedom, they belonged to an "surplus population", the "surplus" who are poor and unemployed, often sick - they cost the state above all money, as can be seen from every average right-wing election campaign speech. It was only when they became delinquent and ended up in prison that these people turned into a useful resource, as Ruth Wilson Gilmore describes it in her book "Golden Gulag".

The women Kim Abeles met during her project had also often lived in precarious conditions before her imprisonment. Very often, says Abeles, women also got into hopeless situations because of men - "wrong friend, wrong place, wrong situation, and you're already in it," she puts it. For example, one of the firefighters was convicted of breaking the arms and legs of a man who abused her child. Such a story is not unusual, she has heard many of it, says Abeles. You imagine lively conversations with the women while sewing or at the campfire, but it was not that easy - there were also wardens in the camp. "It was forbidden to fraternize," laughs the artist. "Of course I fraternized anyway."

Source: F.A.Z. Acquire item rights; Frauke Steffens, Feature correspondent in New York.